Pasteur the Chemist

While he is well known for his many remarkable breakthroughs in the biological sciences, Louis Pasteur got his start working in chemistry. Perhaps unsurprisingly, in the short time he spent on chemical research he made an observation so stunning and original that the unbelieving French Academy required him to perform it again in front of a full assembly of senior scientists. What Pasteur had found was that organic compounds possessed the quality of chirality, or handedness. Just as right and left hands are in many ways the same but, of course, not the same in certain other respects, Pasteur found that certain organic compounds also had this property. He demonstrated this by separating crystals of a compound known as potassium ammonium tartrate into its two “handed” versions. Pasteur was able to separate these two “handed” varieties of the crystals based on their appearance with the aid of a magnifying glass and tweezers. The two sets of crystals shared certain properties, such as solubility and melting point, but differed dramatically in the way they interacted with light. Pasteur speculated that the two “handed” versions were related by a mirror image symmetry, just as human right and left hands are, ideally, mirror image reflections of one another. They were, as the Nobel Prize-winning chemist Roald Hoffmann likes to say, “the same and not the same.”

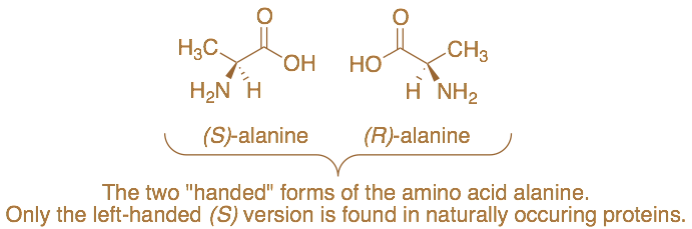

Pastuer went on to do the bulk of his work in biology and the chemical phenomenon of handedness in molecules remained only vaguely appreciated until the Dutch chemist Jacob van’t Hoff offered an explanation in terms of the tetrahedral binding geometry of carbon atoms. In van’t Hoff’s explanation, the quality of handedness could be undestood through the mirror image symmetry possible in tetrahedral carbon, where four different substituents were bound to the central carbon atom. The mirror image molecules are reflections of one another, but are not superimposable and, thus, are not the same.